8 May–5 June 2010

JOHN FURNIVAL

somewhere between poetry and painting

A survey of prints, drawings and collaborations

John Furnival’s prints and drawings connect his antecedents in the Dada and Surrealist movements to his affinities and associations in the early 1960s with the innovators of Concrete poetry, the Beat poets, and the Fluxus and Mail Art movements.

Furnival somehow has avoided falling into any one of these specific categories, styles or movements. Furnival’s distinctive métier is ‘primarily one of ironic precision and evocation’: ‘iconic exactness is combined with a spirit of semantic complexity and irony’, somewhat different from the pared down, minimalist poetics of Concrete poetry. Furnival’s method is a kind of verbal/visual accumulation that takes the reductive qualities of Concrete poetry and subjects it to the accumulative poetics and cut-up collage techniques used by Surrealist and Dada artists in the 1920s and ’30s, and by the generation of Beat poets and writers exemplified by Brion Gysin and William Burroughs. Furnival creates his own idiosyncratic system, saying that ‘my whole work has been involved with the making of a moiré pattern of meaning, the laying of one message over another, unrelated one, to produce a third, unrelated to either.’

Furnival emerged from the Royal College of Art in London in 1959 with an avowed insistence on deliberately exact drawing. His contemporaries included Joe Tilson, Peter Blake, David Hockney, and Ron Kitaj, the RCA pop artists who were inspired by advertising, popular culture, poetry, and mythic figures from the mass media – like Furnival, they too had moved on from the dominant action-painting style of the late 1950s. His work shares many of the concerns of British and American pop art, but his vision is somehow more subtle.

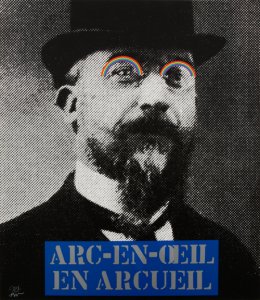

Furnival’s early hand-drawn and hand-written verbal/visual collages – he called them ‘semiotic drawings’ – were witty orchestrations of fragmentary found texts and images, although he said that the words were used in ‘a non-pop way’. As Nicholas Zurbrugg wrote in a catalogue for Furnival’s 2000 exhibition in Verona, one thinks not simply of British pop art, ‘but of more timeless poetic composition, such as the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s early twentieth-century calligrammes… his work simultaneously evokes both the present and the past, highlighting the social and political paradoxes and contradictions of the here and now, while also affectionately referring back to early twentieth-century artists.’

Zurbrugg likened Furnival’s work to the American composer John Cage’s multimedia collages of electronic music, radio broadcasts and TV and film images; to literary collages, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses or William Burroughs’ Nova Express; to the work of those Concrete poets carefully integrating words and images in verbal-visual compositions, such as the Scottish poet, Ian Hamilton Finlay; to the work of language artists, minimal artists or conceptual artists, such as Arakawa, Mel Bochner and Lawrence Weiner; and to the way certain American pop imaging, seen in some works of Jasper Johns, combined the expressionist maximalism of Jackson Pollock’s brushstrokes and the formal minimalism of typographic subject matter.’

John Furnival taught at Bath Academy of Art at Corsham, and latterly at Bath, in its seminal period in the 1960s and 70s. In 1964, he co-founded the press, Openings, with Dom Sylvester Houédard, working with artists and poets in an early move to make art ‘mailable’ – these included Tom Phillips and Edwin Morgan, and also Ian Hamilton Finlay with whom he collaborated for a period for the Wild Hawthorn Press. Furnival participated in the First international Exhibition of Experimental Poetry in Oxford in 1965, and the exhibition that followed – Between Poetry and Painting – organised by Jasia Reichardt at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Dover Street, London in the same year. Henri Chopin was another associate and collaborator, as was Furnival’s great friend, the late American poet/publisher, Jonathan Williams with whom he worked on the folio, St Swithin’s Swivet, and on the still on-going project they started together in the early 1980s, Letters to the Great Dead, with its very particular combination of text and image.