Obsessive Visions

6 October – 3 November 2001

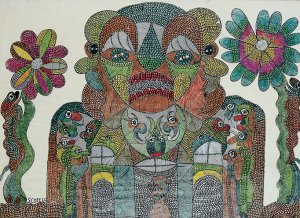

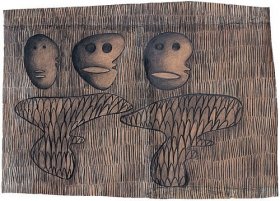

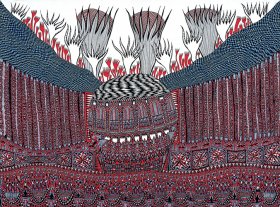

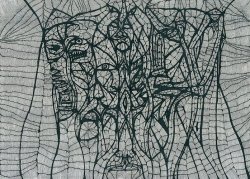

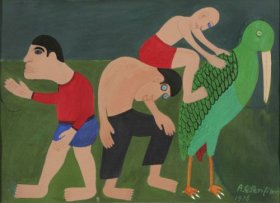

Art Outside the Mainstream

In 1996, England & Co co-curated an exhibition Outsiders & Co with John Maizels to launch the publication of his book Raw Creation. This exhibition, and the sub-title for Maizels’ book, Outsider Art and Beyond, suggested and allowed for the inclusion of artists who had an authentic inner vision, but who were not necessarily Outsiders according to strict definitions of the category. This exhibition explores what has been called an Outsider aesthetic, an art outside the critical and institutional mainstream; but its main criteria is that, in Paul Klee’s words, the artists attempt to ‘make secret visions visible’.

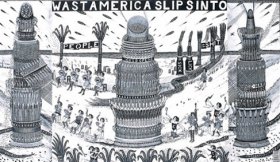

There are works by both acknowledged true Outsiders such as Scottie Wilson and Madge Gill, together with works by artists who are to various degrees more educated and culturally aware. George Melly has described these artists as the educated cousins of the Outsiders, and Jean Dubuffet assigned the name Neuve Invention to works that fell just outside the borders of his own original rigorous categorisation of Art Brut. Roger Cardinal, in his seminal book Outsider Art, its title re-naming Art Brut, wrote that this new art (an art that has always been) proliferates around the outskirts of the cultural city; his book ends with with the busy, uneven clattering made by the nameless creators presently engaged in erecting alternative realities, sounds which are yet too disparate for us to apprehend as a single message the siege of the cultural city is underway.

A basic definition of Outsider art is that the works are made by untrained artists who work for and by themselves, knowing little of cultural history or the tradition of Fine Art. By its very nature it is not uniform; the extreme individuality of its creators makes it disparate. The curators of Art Unsolved, an exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, pointed out in the catalogue that some Outsider artists suffer from psychiatric conditions, some are socially excluded, a small number are well educated but may have experienced poverty and some are driven by an inner spirit Outsider artists focus directly on their inner vision, blocking out the distractions that condition their mainstream colleagues, generally unaware and in most cases unconcerned by their own exclusion The term Outsider Art only exists in relation to the establishments at the inside of the art world, the centre in contrast to the edge.

As Outsider artists become known, their once secret creativity is exposed and they can become knowing, their innocence possibly tarnished by discovery and acclaim. Scottie Wilson, for example, was affected by his success and growing fame in the 1950s and 60s, his pictures becoming increasingly decorative as he became aware of the possibilities of selling his works, only to regain intensity after a breakdown later in his life. Albert Louden has deservedly achieved success and recognition for his work, which has led to the comment that this Outsider is also an insider. This is always going to be an area of contention, but as George Melly once wrote in Raw Vision magazine, to praise and exhibit an Outsider, reveal that there is a market for their work you may lose them. Should you deliberately keep them in the dark? I think not. To deny human beings happiness or satisfaction in order simply to preserve the purity of isolated obsession is surely wrong. We are at liberty to celebrate the inner truth of Outsider Art and adhere strictly to what defines it, but we must never seek to confine those who produce it to a kind of mental monastery.

There is also the conundrum that many educated artists of the 20th century and of today have sought to strip away the sophistication of their training in attempts to achieve authenticity in their work, and have been inspired by both primitive and untrained art. Picasso was influenced by African and Polynesian art; and the Surrealists, experimenting with automatism, were fascinated by Dr Hans Prinzhorn’s book Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Paul Klee was affected by the spontaneous art of children; and British artists working in St Ives in the late 1920s and 1930s, such as Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, were influenced by the work of the self-taught Alfred Wallis. As Jon Thompson pointed out in his essay Peripheral Visions The Limits of Modernism, for the artists who have thus far been designated Art Brut or Outsider artists, the achievement of this state of singularity has come comparatively easily. They were, in this respect, fortunate to be without the encumbrances of schooling and culturisation. For the schooled artist, true singularity is always going to be hard won.

In the all-pervasive mass culture of the 21st century it is now almost impossible to describe Outsider art as an art without precedent or tradition or to encounter an artist totally free from cultural reference. Labels are inevitably inadequate in defining movements or schools in art history as the boundaries of a definition are too often blurred Outsider Art is an expression that has to an extent been hijacked by the art press and art market and used as a convenient catch-all label. As Jean Dubuffet wrote so perceptively: Art does not lie down on the bed that is made for it: it runs away as soon as one says its name; it loves to be incognito, its best moments are when it forgets what it is called.

Jane England, October 2001

Illustrated catalogue available.